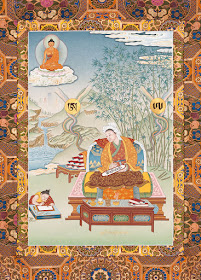

Thönmi Sambhota Thangka description

This is a traditional thangka* painting, which was especially commissioned

by Tashi Mannox on the rarely depicted great calligrapher and scholar Thönmi

Sambhota.

Sambhota is reputed to be a historical figure responsible for developing the foundation of

the Tibetan writing systems in the seventh century A.D, which form the basis of

the Tibetan language today. See below for the

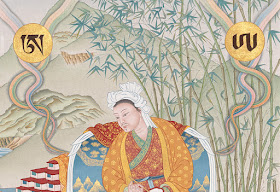

In this thangka, Thönmi Sambhota is shown as the main figure wearing

traditional attire of a Tibetan layperson, though wears a white turban in

reference to his many years spent in Northern India studying chiefly Sanskrit with

Brahmins and Pandits.

He holds in his lap a tablet inscribed with a rendition of a Mani

mantra, oṃ

maṇipadme hūṃ, which was presented to Dharmaraja King Songtsen Gampo as the first

sample he created of the Tibetan Uchen script. The original writing of this

mantra was carved on a rock in Rigsum Gompo temple in central Tibet, which was

unfortunately destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.

On a table before Sambhota are laid out calligraphy implements such as

ink and bamboo pens, cut from the bamboo grove behind him. Tibetan manuscripts

also sit before and behind referring to Sambhota’s scholarly achievements and

the Tibetan grammar and punctuation he composed.

Emanating from Sambhota on rainbow beams are two golden disks marked

with the letter Aa ཨ the last letter of the Tibetan alphabet, which is also

considered the essence and expression of the entire alphabet in one. On the left is Aa ཨ in the classical Uchen

script and on the right is the same letter Aa ཨ in the Umed class of scripts.

These represent the two main groups of script styles he created and still in

use to the present day.

The thangka painter Sahil Bhopal entrusted Tashi to personally add the two principle

letters Aa ཨ to the golden disks, as well as the Mani mantra within the thangka.

To Sambhota’s below right is a student in practice of calligraphy. While

above is a scene of nature, more typical of the Karma Gadri style of thangka

painting, with trees and a cascading waterfall bringing prosperity.

To Sambhota’s below right is a student in practice of calligraphy. While

above is a scene of nature, more typical of the Karma Gadri style of thangka

painting, with trees and a cascading waterfall bringing prosperity. In the far distance are five mountains of Manjushri, the deity of learning, or can also represent the five Wisdom Buddha families.

In the sky above is Sakymuni

Buddha, who crowns Thönmi Sambhota representing his Buddhist belonging, and

motivation to benefit all.

*Tibetan thangka painting

is one of the great arts of Asia. A particular stylistic development of

painting in natural mineral media, normally on cloth which is mounted in a

brocade frame, designed to role up as a portable scroll.

Thangkas are typically rich

in iconography of their religious content that communicate the highest Buddhist

ideals, often as a visual aid to be meditated upon or to depict historical

figures and spiritual events. For a Tibetan Buddhist, thangkas are considered inspirational

sacred paintings in their physical support to a practitioner as an embodiment

of enlightenment.

History of the Tibetan Writing System

It was during the seventh century reign of Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo,

and under his direction, that the first iteration of what would become the

modern day Tibetan written language came into existence. Prior to this Tibetans

had used Mayig, a comparatively

rudimentary system. But Songtsen Gampo was faced with the task of translating

the wealth of existing Buddhist Sanskrit texts into Tibetan, and needed a

coherent writing system with sufficiently rich symbolism. He turned to minister

and great scholar, Thönmi Sambhota, who along with sixteen other wise ministers

travelled to India to study Sanskrit. Only Sambhota would return suitably

qualified. His journey had proved fruitful, however, and a new Tibetan writing

system, based loosely on Indic Sanskrit was established. It is worth noting

that the Tibetan spoken language remained the same; only written language was

renovated. Sambhota had conceived an alphabet and standardised writing

conventions, including grammar and punctuation, and would later also produce

the first iteration of both the Uchen and Umed forms.

Different script styles developed over the next several hundred years.

In the early ninth century the Tibetan script underwent another transformation

and ‘Old Tibetan’ was standardised to ‘Classical Tibetan’. One thousand years

passed, yet Tibetan calligraphy persevered, steadily evolving towards its

contemporary form. By the nineteenth century the models of Uchen and Umed, the

two main Tibetan script styles, had ossified and bore the exact

proportions still in use today.

Tibetan Calligraphy

& Tibetan Buddhism

From the offset, then, a notable bond existed between the Tibetan

writing system and Buddhism – its creation being motivated primarily by a need

to conserve and decipher Sanskrit Buddhist manuscripts. To limit calligraphy

and Tibetan Buddhism (and by association Tibetan culture’s) connection to

simply a functional conception, however, does not do justice to their

relationship. The two are largely inseparable and have remained so to the

present day. Tibetan Buddhism is considered a ‘live’ tradition, comprised of

many lineages in which a master will impress the totality of a line’s knowledge

on a disciple. The lineage is also considered fluid, as the disciple then

realises the wisdom of these teachings through meditation. Clearly, the

academic and meditative aspects of Tibetan Buddhism are closely linked.

Calligraphy’s role in this relationship as a key by which existing Buddhist

teachings are unlocked compounds its status. Developing a written language

certainly also had administrational benefits for the empire, with its use in

legal and historical documents.

-Luke Purdye

No comments:

Post a Comment